In this post, I want to emphasize how much we are in danger of losing, how much of early digital cultural material is evaporating. I don't want to suggest that the loss is something that is individuated and endemic to digital work, as ample scholarly work has proved that not to be the case. Instead, I want to argue that the small scale, scholarly projects that are crucial to the early days of digital humanities are particularly vulnerable in large part because they are formed outside of institutional structures. These are often one off, activist digital projects that scholars put up on personal servers or purchased webspace. Those who worked on these projects did not necessarily identify as digital humanists and often left the projects without an archiving plan when they were "finished." Yet these projects, in content and design, tell us a great deal about early digital scholarly production and remain valuable artifacts of the period in which they were produced.

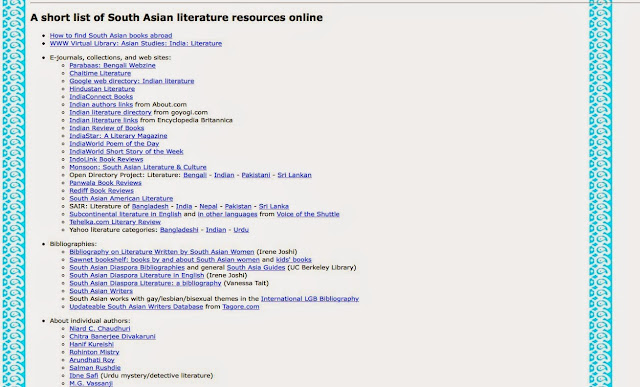

When I was writing my book I often looked to Alan Liu's Voice of the Shuttle website to locate older dh projects. If you use the internet archive to look at older versions of the Voice of the Shuttle you can track digital projects that appear and disappear over time. Since I work in African-American literature, I was very interested in the section originally titled "Afro American" Minority Literatures. The earliest archive of this section is from January 19, 2000 and contains, among various subtopics, a section dedicated to Maya Angelou.

see https://web.archive.org/web/20000119213716/http://vos.ucsb.edu/shuttle/eng-min.html

All three original sources are in existence, but have been moved to other servers. The Scott Williams page is of particular interest because it is suggests the interdisciplinary, activist roots of many of the projects I am cataloging.

The project appears to have been originated in 1998 by Williams using a pseudonym, bonVìbré Prosim.

See https://web.archive.org/web/19981203160317/http://members.aol.com/bonvibre/

According to the internet archive records, it appears that the pages were migrated from their original aol home to Williams' personal web space in the Math Department at the University of Buffalo around the end of 1999. The pages have not been updated since 2000.

When the pages were migrated they were expanded under the auspices of the Circle Brotherhood Association.

All three original sources are in existence, but have been moved to other servers. The Scott Williams page is of particular interest because it is suggests the interdisciplinary, activist roots of many of the projects I am cataloging.

The project appears to have been originated in 1998 by Williams using a pseudonym, bonVìbré Prosim.

See https://web.archive.org/web/19981203160317/http://members.aol.com/bonvibre/

According to the internet archive records, it appears that the pages were migrated from their original aol home to Williams' personal web space in the Math Department at the University of Buffalo around the end of 1999. The pages have not been updated since 2000.

When the pages were migrated they were expanded under the auspices of the Circle Brotherhood Association.

Like many early digital sites, the Circle's website is an interesting blend of activism, social outreach and cultural documents. Of particular interest is the focus on local history of African Americans in Western New York and the emphasis on community outreach, with references to the Million Man March and fatherhood activism.

The Circle Brotherhood Association pages are fascinating early digital activist history that deserve preservation and additional exploration, and I hope that someone who works in the nexus of the fields of Black activism, literature and community will provide the work needed to examine this resource.

Given the pages' location, however, it is clear that this early marker of digital history is in danger of disappearance. The pages exist on a university server, but under Scott Williams' personal folders. Professor Williams is no longer listed as a faculty member at the University of Buffalo, suggesting he has since retired and his web pages exist in a sort of limbo. The pages are clearly experiencing deterioration as the current site no longer links to the Malcolm X pages. Unless the university has plans to archive the materials, they will eventually disappear.

It is true that much of the site is preserved on the internet archive. I am unsure, however, what it says about us as a field or area of study that we have effectively off loaded the preservation of much of our field's work to even a fabulous organization such as the ia. As we think about how to preserve, we must continue to press to think about what is preserved, as small activist work like the Circle Brotherhood Association pages provide cultural context for what digital diversity meant in the late 1990s.